Great Variations in Aging Process (Not Just Lifespan) Among Different Animals

Fluted giant clam. Clams can live indefinitely - growing larger and more reproductive with age. Oldest known, 507 years. Wikimedia Commons cc-by-sa-2.0.

Aging varies greatly among different species - not just lifespan, but the whole aging process. That's good news. If aging were similar in all species, it might be a consequence of life itself (such as an inevitable accumulation of errors in cell reproduction). But different animals have evolved great variations in aging (including rare cases of species that do not age at all).

Recently scientist and blogger Dr.Josh Mitteldorf published an article about aging across animal species (and some plants) - see link below. That article doesn't deal with human aging, so we added a background note.

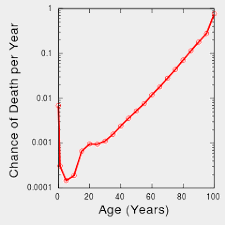

Human Aging: The Gompertz Curve

Around 1825 Benjamin Gompertz published the observation that in peaceful times (without war, famine, or epidemics), the human death rate doubles about every 8 years. This is remarkable constant for most of the human lifespan (from before 30 to after 90), as the surprisingly straight line in the graph indicates. If the death rate at age 30 stayed the same and did not increase later, many of us would live for hundreds of years. Humans and some animals have a Gompertz-type mortality, but other species have aging patterns that are very, very different, from human aging and from each other.

Dr. Mitteldorf believes that aging evolved in humans and other species, for group survival. It may have been selected to protect predator species from famine due to population overshoot, which could lead to extinction of the prey and resulting extinction of the predator. This evolutionary theory might explain why aging is less important in plants than in animals. And the very different patterns of aging in different species have been maintained by evolution over thousands of generations.

There are other theories if aging, for example: accumulation of random errors (mentioned above); no evolutionary pressure to keep animals alive after reproduction (and care for the young, if any); and selection of genes that are beneficial or necessary for life, but also cause harmful effects that lead to aging. And scientists have proposed many specific mechanisms, such as senescent cells, one of the most important lines of research today; senescent cells have been damaged and can no longer reproduce, but they can secrete abnormal chemicals that damage the body. Of course more than one of the various theories could be contributing to the aging process.

Aging Across Species: Some Examples

Here are a few examples from Dr. Mitteldorf's paper, The Varieties of Aging in Nature, posted 2017-12-06:

- Senicula is a plant that grows in Sweden. It's life expectancy is about 75 years. If you have plants that are 74 years old, their remaining life expectancy is 75 more years. Some of the plants are over 200 years old, and their life expectancy is still the same, 75 more years.

- Clams can keep growing (and getting larger) indefinitely - and they have growth rings that can be counted to tell how old they have grown. The oldest clam known is 507 years old. The older clams release many more fertile eggs than younger ones, and a few of them can maintain a whole community.

- Many animals, like Pacific salmon, reproduce just once in a lifetime, then usually die. Animals that reproduce just once in their lifetime are called semelparous. Some of these animals do not eat after reproduction, and die of starvation, instead of other kinds of aging.

- A small flatworm called Planaria, if starved, will begin to consume itself, until only the brain and nerve cells remain. Then if fed, it will grow back - but as a young worm. It can do this again and again, remaining young long after the worms that were continuously fed had died of old age.

- And there's more, equally bizarre. See the article about aging or not in: the octopus; "the immortal jellyfish"; hydra; bees; and the paramecium, a one-celled animal that separates sex and reproduction entirely.

Note the more than 100 comments, mostly from readers well informed about aging and aging research.

And note the new book by Josh Mitteldorf and Dorian Sagan, Cracking the Aging Code: The New Science of Growing Old - And What It Means for Staying Young, June 2017.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. But we suggest linking here instead of copying our text, to show the latest information.